Universal Testing Machines generate data that gets used for QC decisions, supplier approvals, and audit evidence. If the force system or strain measurement drifts, results can look “normal” while quietly moving out of tolerance. When that happens, the problem is rarely caught at the moment of testing. It shows up later, during an audit, a customer challenge, a failed correlation, or a retest that does not match.

Calibration is how labs tie measurements back to a reference through a documented chain of calibrations, with stated uncertainty. That traceability concept is central to how metrology works, including NIST's definition of traceability as an unbroken, documented chain linked to a reference standard. For UTMs, this usually means verifying the force-measuring system to recognized standards like ASTM E4 or ISO 7500-1.

Your calibration interval decisions have practical consequences. They affect whether test data is accepted during audits and contract reviews, how much downtime you schedule (planned service versus urgent fixes), and how often you end up paying for rework, extra investigations, or repeat testing when results are questioned.

What “Calibration” Means for a Universal Testing Machine

In practice, people use “calibration” as a catch-all term. For a universal testing machine, it helps to separate three things because they lead to different reports and different expectations in audits.

Calibration is the process of comparing the machine's indicated values to a traceable reference over a defined range and documenting the measurement error. The output is a calibration record that shows what was checked, what reference equipment was used, the test points and range, and the resulting performance.

Verification is a confirmation that the system meets a stated requirement or tolerance. In many labs, verification is tied to a specific standard or accuracy class and ends with a pass or fail decision for a defined range.

Adjustment is any change made to bring the system back into tolerance. This may involve changing settings, replacing components, or correcting the measurement chain. After an adjustment, the machine should be checked again to confirm performance.

Two terms in calibration reports matter in audits because they show what the machine was doing during real testing:

- As Found: performance before any changes were made

- As Left: performance after adjustment or service

If the “as found” results are out of tolerance, that can trigger internal review because it means some past test work may have been run on a machine that was not meeting requirements.

For most universal testing machines, calibration and verification usually focus on the measurement systems that drive test results:

- Force measurement system: load cell or force transducer, signal conditioning, and the indicated force readout

- Control and readout chain: controller, amplifier, display or software reporting the measured values

- Test-critical sensors: devices that can affect reporting, such as extensometers or displacement measurement hardware, when they are used for strain-based results

The Standards That Usually Define Universal Testing Machine Calibration

In most labs, calibration and verification for a universal testing machine starts with the force measurement system. Two standards are referenced most often, depending on the market, customer requirements, and audit expectations.

ASTM E4 is the common reference in North America for verifying the force-measuring system in tension and compression testing machines. It defines how the force system is checked across a verified range using traceable reference equipment and what performance limits apply over that range.

ISO 7500-1 is widely used internationally and is also common in North American labs, especially when work supports global programs. It covers verification of the force measurement system and assigns accuracy classes (for example, Class 1), which labs may reference in quality procedures, specifications, or customer requirements.

These force standards focus on how accurately the machine measures applied force through the measurement chain, such as the load cell or force transducer, signal conditioning, and the displayed or recorded force value. They do not define how to run a specific material test, how to prepare specimens, or how to calculate or report material properties. Test methods come from separate standards such as ASTM, ISO, or customer procedures.

A separate point that often gets confused in audits is ISO/IEC 17025. It does not calibrate the machine by itself. It is a framework for laboratory competence, traceability, and reporting, meaning it governs how a calibration provider demonstrates technical capability, documents traceability, and states measurement uncertainty. In other words, ASTM E4 and ISO 7500-1 define what the force-system verification looks like, while ISO/IEC 17025 defines how a competent lab should perform and document that work.

If your testing relies on strain or displacement results, additional standards may come into scope, such as ASTM E83 / ISO 9513 for extensometers and ASTM E1012 for frame alignment. These are usually treated as separate items from force verification, depending on what your test program actually reports.

Typical Calibration Intervals: What Is Common and Why

A common starting point for a universal testing machine is 12 months for force verification. Many labs use an annual cycle because it aligns with internal audits, customer review cycles, and the practical reality of scheduling downtime. Both ASTM E4 and ISO 7500-1 are commonly applied with a 12-month interval as a typical maximum unless there is a clear reason to set a different schedule.

Intervals are often shortened when the machine is heavily used, when results support high-risk programs, or when the lab is working to tight internal tolerances. The more often a machine runs near capacity, the more likely the force measurement system and mechanical stack will show drift or wear that becomes visible in “as found” results over time. General calibration guidance also supports setting intervals based on stability, usage, and risk rather than treating one number as universal.

Beyond the calendar, most labs treat certain events as automatic triggers for recalibration or verification, even if the next due date is months away:

- Relocation or reinstallation (site move, new foundation, new power conditions)

- Major repair or rebuild, including controller work that affects the measurement chain

- Load cell or force transducer replacement

- Overload events or suspected mechanical damage

- Abnormal results, failed correlations, or sudden increases in scatter

A clean way to set intervals without making it sound like policy language is to use two inputs: (1) how critical the data is, and (2) what your own history says. Start with annual verification, review the “as found” trend from prior calibrations, and adjust the interval if drift or failures show up. That approach matches how metrology programs build confidence over time: periodic recalibration is used to detect uncertainty growth and manage the risk of bad measurement results.

What Else May Need Calibration Besides Force

Force verification is only one part of keeping a universal testing machine audit-ready. Auditors and customers often look at the full measurement chain that supports the values you report, especially when strain, modulus, or displacement is part of acceptance criteria.

Extensometers (ASTM E83 / ISO 9513)

If your reports include strain, elongation, yield by offset strain, or modulus, the extensometer is a primary measurement device, not an accessory. ASTM E83 and ISO 9513 define how extensometers are calibrated and classified by accuracy. This matters most for modulus work, tight strain limits, and any program where small strain errors can change pass or fail decisions.

Frame Alignment (ASTM E1012)

Alignment checks matter when bending or off-axis loading can influence results. ASTM E1012 describes alignment verification for testing frames, which helps control unintended bending strains that can distort tensile or compression data. This is most relevant for critical programs, higher-force testing, and labs that see unexplained scatter between machines.

Displacement and Speed Measurement (When Applicable)

Some setups report crosshead displacement as part of the test record, or rely on machine speed for method compliance. If displacement or speed is part of the specification, you may need separate verification or calibration of the displacement measurement device or the speed control system. This is more common in method-driven QA programs, automated test setups, and situations where stroke or travel is part of acceptance.

Audit-Ready Files: What Documentation Should Look Like

An “audit-ready” calibration file is not about having more paperwork. It is about having the right details, in a format that lets an auditor or customer confirm three things quickly: what was checked, whether it passed, and whether the results are traceable.

What A Calibration Package Should Include

Most auditors expect to see the following elements, even if the report layout differs by provider:

- Standard referenced (for example, ASTM E4, ISO 7500-1, ASTM E83, ISO 9513)

- Scope and range covered (the verified force range, points used, and which modes were covered, such as tension and compression)

- Machine identification (model, serial number, asset ID, location)

- Reference equipment identification (reference load cell or proving device IDs, calibration status, and traceability chain)

- Measurement uncertainty (or a clear uncertainty statement) and the stated accuracy class or tolerance basis

- Results summary with a clear conclusion, such as pass/fail or a tolerance statement for the verified range

If any corrections were made, auditors usually want the evidence:

- As Found and As Left results

- A short note describing what was adjusted or replaced

- Any corrective action record if “as found” was out of tolerance, especially if the machine was used for production testing during the affected period

How To Keep Records Easy To Audit

Keep calibration records in one place with a predictable structure. The simplest approach is one folder per machine, with subfolders by year, and filenames that make the key details obvious without opening the PDF.

A practical naming format looks like:

- MachineID_ForceVerification_ASTM-E4_2025-06-14.pdf

- MachineID_Extensometer_ISO-9513_2025-06-14.pdf

If your quality system uses revisions, keep the latest certificate clearly marked and avoid multiple “final” versions in the same folder. If a certificate is replaced or corrected, store the older version as superseded rather than deleting it. That makes audits faster and prevents confusion about which certificate was valid at the time of testing.

OEM Vs Third-Party Calibration: Practical Differences

Both OEM and third-party calibration can meet audit expectations if the work is done to the right standard and the documentation is solid. The best choice usually comes down to warranty, turnaround, logistics, and how your lab needs to run.

When OEM Service Makes Sense

OEM calibration means the original manufacturer (or an authorized service channel) performs the work. This option is often a good fit when:

- Warranty or service terms matter. Some manufacturers tie warranty or extended warranty programs to calibration performed through authorized facilities.

- You want manufacturer-defined procedures and spec coverage. OEM programs may include test points and checks aligned to the manufacturer's full specifications, not just a minimal compliance set.

- You are bundling calibration with refurbishment. OEM service is often paired with firmware updates, replacements with OEM parts, and model-specific adjustments.

One tradeoff is time. OEM calibration can take longer in some cases because calibration is not always the manufacturer's primary line of business, and turnaround can stretch depending on workload and shipping.

When An Accredited Third-Party Makes Sense

Third-party calibration is performed by an independent calibration provider. It can be a strong fit when:

- Downtime needs to stay low. Many third-party providers offer faster scheduling options and, in some cases, on-site work.

- You run multiple brands. A single provider can often service a mixed fleet under one vendor relationship and one documentation format.

- You want ISO/IEC 17025-aligned reporting. Accreditation is often used as a quick filter for competence, traceability, and uncertainty reporting.

How To Compare Providers Without Guesswork

Instead of “OEM vs third-party” as a label, compare on specifics:

- Accreditation scope: Does the provider's scope match what you need (force, extensometer, alignment) and the ranges you use?

- Traceability and uncertainty: Do certificates clearly state traceability and measurement uncertainty?

- Report quality: Does the report name the standard, list the verified range, include IDs/serials, and give clear pass/fail or tolerance conclusions?

- Turnaround and support: How fast can they schedule, and what happens if “as found” is out of tolerance?

Industry Scenarios: Where Requirements Tend To Be Stricter

Calibration expectations change based on how the test data is used. The higher the risk and the tighter the acceptance criteria, the more attention you will see on interval, documentation detail, and who performed the work.

Aerospace And Defense

Aerospace and defense programs tend to be strict because test results often support qualification, certification, and safety-critical decisions.

What typically changes:

- Shorter intervals or tighter internal rules if the machine supports production release testing

- More documentation in the calibration package, including clear scope, uncertainty statements, and “as found” results

- Accredited providers are commonly preferred, especially when audits require traceability and uncertainty to be stated in a consistent way

- Extensometer and alignment evidence is more likely to be requested when modulus, strain-based acceptance, or low scatter requirements are in play

Automotive And Manufacturing QA

Automotive and general manufacturing QA is usually driven by repeatability, supplier controls, and customer audits.

What typically changes:

- Interval decisions follow production tempo. If the machine runs daily, many plants keep intervals conservative and watch drift trends

- Supplier-audit readiness matters. Customers often ask for calibration history, not just the latest certificate

- Consistency across sites becomes a focus, meaning the same standards, the same ranges, and similar report formats across facilities

- Strain measurement gets attention when yield by offset strain, elongation limits, or modulus are tied to pass or fail

Construction Materials And Metals Testing

Construction materials and metals testing can look straightforward, but contract acceptance work raises the bar fast.

What typically changes:

- Clear pass or fail language and a verified range that matches the loads actually used for contract tests

- Retest risk drives discipline. If results are disputed, the first question is often whether the machine and sensors were in tolerance at the time of test

- Witness testing or customer oversight shows up more often on high-value projects, which increases pressure on clean records and current certificates

A simple way to think about it: if your test report can block a shipment, reject a lot, or support a certification decision, your calibration program usually needs tighter intervals, deeper records, and stronger traceability.

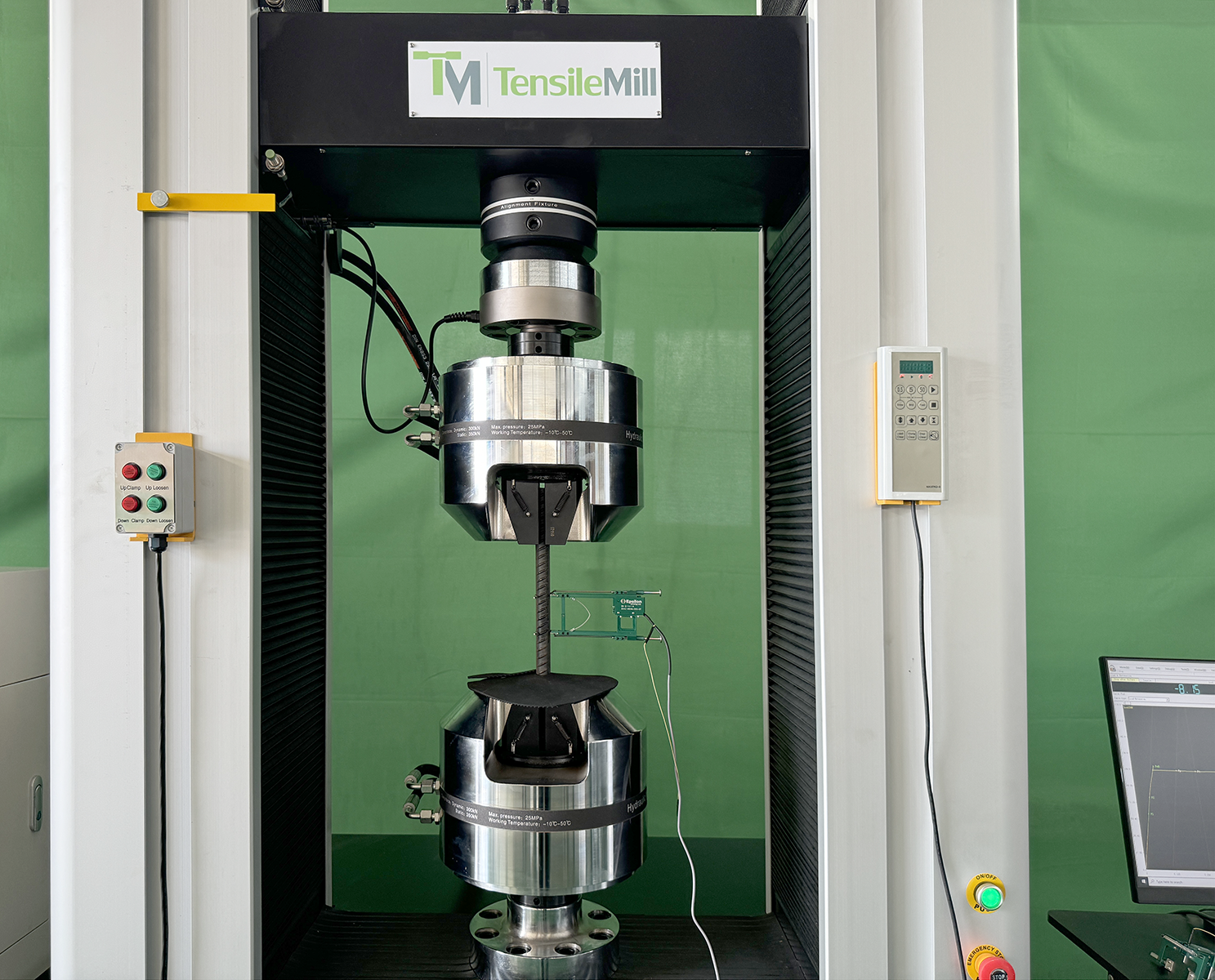

Calibration And Certification Support

TensileMill CNC coordinates calibration and certification for Universal Testing Machines, load cells, extensometers, and related testing equipment, whether the system was supplied by TensileMill CNC or another manufacturer. Support commonly includes force verification to ASTM E4 and ISO 7500-1, frame alignment checks to ASTM E1012, and extensometer calibration to ASTM E83 and ISO 9513, with ISO/IEC 17025-aligned documentation packages through accredited partners. If you need help planning calibration for an upcoming audit or project, you can request a quote or review details on our testing equipment certification page.

Keeping Your Calibration Program Audit-Ready

A good calibration program is really about avoiding surprises. When a universal testing machine stays within spec, your data holds up in audits and customer reviews, and you are less likely to get pulled into retests, investigations, or “why do these results not match last month?” conversations. It also protects day-to-day operations. Problems show up as a controlled finding on a certificate, not as a failed install, a halted production run, or a last-minute scramble before an audit.

There is no single interval that fits every lab. A machine that runs a few tests a week is not managed the same way as one that runs all day on tight tolerances, supports contract acceptance, or feeds safety-critical programs. Most teams start with a yearly baseline, then adjust based on usage, past “as found” trends, repairs, relocations, overload events, and what their customers or audit programs actually require.

This article is meant as a practical overview, not a substitute for your quality system or contract requirements. If your work is governed by a customer specification, an internal QMS, an accreditation program, or local authority expectations, use those documents as the final reference for interval and documentation rules.