Sample preparation is a key aspect of material testing. It makes sure specimens meet specific standards for accurate evaluations. The complexity of this preparation varies with the type of test - from straightforward procedures to complex processes. For assessments such as tensile, impact, and hardness testing, samples are typically prepared using CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machines.

CNC operators, also known as CNC machinists, are professionals responsible for setting up, operating, and maintaining CNC equipment. Their expertise allows laboratories to obtain precise test specimens, free of defects like tool marks or internal deformations, necessary to achieve reliable results.

This article is intended to provide an in-depth look at the profession of CNC operators, exploring who they are, what they do, how they can become one, and more.

Understanding the Role of CNC Operators in Material Testing

Precision starts long before the test. CNC machinists act as the first line of quality, preparing high-accuracy specimens that determine test results' reliability. Their contribution is technical, critical, and often underestimated-yet without it, even the most advanced testing systems cannot perform effectively.

Definition and Overview

Before any sample can undergo a tensile, impact, or hardness test, it must first be shaped to exact dimensions. CNC operators program and operate computer-controlled machines to produce specimens that meet industry standards such as ASTM E8 or ISO 6892. They work closely with engineers and lab personnel to verify that each sample is created according to blueprint specifications, typically within tolerances of ±0.01 mm.

Key Responsibilities

CNC operators have well-defined responsibilities. Their tasks combine technical precision, interpretive skill, and preventative care to meet laboratories' exact standards. Let us examine a few of them closely:

1. Setting Up and Operating CNC Machines

CNC machinists begin their workflow by configuring the machine for the specific task at hand. This involves selecting the correct tooling (such as end mills or carbide inserts), setting material parameters (like feed rate and cutting speed), and loading machine programs. When producing tensile test specimens, for example, the operator must make certain that the material is securely clamped and aligned before machining begins. One misalignment can lead to inaccurate cuts or material deformation. They also run initial test passes to confirm the toolpaths and that everything works correctly before starting full-scale production.

2. Interpreting Technical Drawings and Blueprints

Accurate interpretation of engineering drawings is necessary to manufacture valid test specimens. CNC operators must understand dimensions, tolerances, geometric dimensioning and tolerance (GD&T), and surface finish requirements. When creating notched samples for Charpy or Izod impact tests, a small variation - such as an incorrect notch radius or depth - can invalidate the results. Operators may work with both 2D mechanical blueprints and 3D CAD models, often using them side-by-side to guarantee that their machine programming matches the intended design.

3. Assuring Dimensional Accuracy and Integrity

Dimensional precision is not optional in material testing - it is necessary. CNC operators use tools such as digital micrometers, dial calipers, height gauges, and coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) to check the final dimensions of each specimen. A tolerance of ±0.01 mm might be required for certain critical features. After machining, the operator inspects the specimen not just for correct dimensions but also for surface quality, burrs, or microcracks that could affect the testing outcome. They document these results for traceability and repeatability.

4. Performing Routine Maintenance on CNC Equipment

Well-maintained machines are crucial to consistent results. CNC machinists are tasked with performing scheduled maintenance - this includes cleaning chips and coolant residue, checking spindle alignment, calibrating zero points, and monitoring tool wear. A miscalibrated machine can introduce consistent errors over multiple specimens. Operators also keep maintenance logs, which help identify recurring issues and reduce unexpected machine downtime that could delay critical testing workflows.

Skills and Qualifications Required for CNC Operators

The success of a CNC operator in the material testing industry depends on more than just machine knowledge. It is a combination of technical skills, proper training, and personal discipline. Every operator must meet certain qualifications to certify that samples are prepared with the highest accuracy and consistency - factors that directly affect testing results.

Technical Skills

To consistently create specimens that meet strict standards, CNC machinists must be technically proficient. Their ability to control machines and interpret commands determines the quality of every cut.

Most CNC machines operate using G-code, a programming language that tells the machine what movements to make. Operators need to understand G-code syntax and logic to troubleshoot errors and customize programs for different sample types. They must also know how to work with various materials - for example, adjusting speed and feed rates when switching from steel to soft metals like aluminum or copper.

Another core part of the job involves reading technical drawings and 3D CAD files. Operators use these documents to visualize the shape, size, and critical features of each sample - such as shoulder-to-gauge length in tensile bars or notch angles in impact specimens. This understanding allows them to accurately translate digital designs into physical results.

Educational Background

While some skills are developed on the job, formal training builds a strong foundation for success. Basic education and specialized instruction are usually expected.

Most CNC operators hold at least a high school diploma or GED. However, many employers now favor candidates with vocational school diplomas or associate degrees in manufacturing technology, mechanical engineering, or machining. Certification programs - such as those from NIMS (National Institute for Metalworking Skills) or community colleges - can greatly improve a candidate’s competitiveness and demonstrate core competencies like machine setup, safety, and programming.

Entry-level roles may be available with minimal experience, but technical labs in material testing often require prior exposure to precision machining due to the tight tolerances involved.

In material testing, even the slightest error can affect a test's outcome. That is why attention to detail is not just an excellent trait - it is a requirement.

CNC machinists must stay alert throughout the machining process, carefully monitoring cutting conditions, tool wear, and output consistency. They often work with tolerances as small as ±0.01 mm, which requires double-checking measurements and tool settings frequently. If a specimen for tensile testing is off by even 0.05 mm, the entire result can be negatively affected.

Operators also need to keep records, verify test sample labeling, and make sure no visible imperfections - such as burrs or surface scratches - are left behind. This focus on detail guarantees that the lab receives dimensionally accurate and test-ready samples.

Career Path and Advancement Opportunities for CNC Machinists in Material Testing

CNC operators in the material testing industry have a clear and strategic career progression. The path typically starts with hands-on CNC equipment operation and extends into technical, supervisory, or specialized quality-focused roles. Advancement depends on skill, experience, and familiarity with precision manufacturing standards used in testing laboratories.

Entry-Level Positions

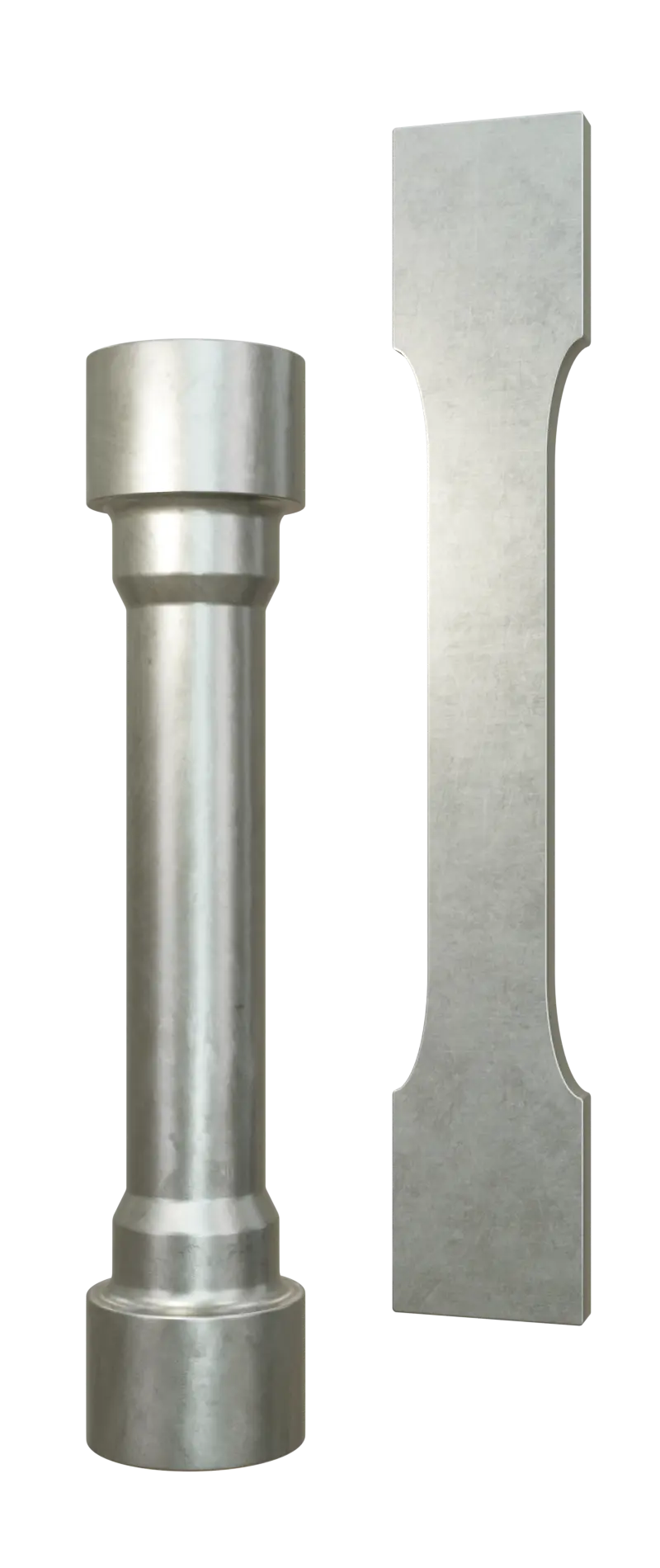

New professionals usually begin as CNC machine machinists or machining technicians. These roles involve setting up and operating CNC mills or lathes to produce standardized specimens used in mechanical tests such as tensile, compression, impact, and hardness testing.

At this stage, operators gain:

- Experience with different materials (aluminum, stainless steel, polymers, composites)

- Understanding of sample types like dog-bone specimens (ASTM E8), Charpy impact bars (ASTM E23), and flat punch samples for microhardness

- Familiarity with ISO/ASTM dimensioning standards and lab-specific tolerances

- Basic quality control practices, such as checking cut tolerances with calipers or micrometers

Depending on the facility, entry-level machinists may also assist with minor machine maintenance or program adjustments under supervision.

Advancement Opportunities

With 2–5 years of experience, operators can move into roles involving deeper technical knowledge and broader responsibility. These positions are typically available in material testing labs, quality control departments, or precision machining companies that serve testing facilities.

CNC Programmer

CNC programming is a common next step. This role involves generating and optimizing G-code or CAM software outputs to automate sample production. Programmers also test tool paths, simulate cutting operations, and reduce machine time without compromising tolerances.

Quality Control Inspector (Sample Dimensioning)

Another route is dimensional inspection. Inspectors in material testing environments use high-precision tools (digital height gauges, profilometers, CMMs) to verify sample geometry. They verify that notches, radii, thickness, and gauge lengths meet required test specs, flagging even minor deviations before samples reach the testing bench.

Production Lead or Supervisor

Operators with strong organizational and technical skills may be promoted to oversee other operators, assign workloads, manage machine performance, and report to lab engineers. These roles often involve communication with quality assurance teams and real-time problem-solving in fast-paced environments.

Specialization Areas

Material testing laboratories value technical specialization. These areas provide a professional focus but also make operators more valuable in precision-driven fields.

Advanced CNC Programming for Specimen Production

Specialists in this area handle highly complex samples, multi-axis operations, or small-batch prototyping for research. They may use CAD/CAM software to develop fixtures, optimize surface finishes for microscopy testing, or automate sequences for repeatable accuracy.

Machine Maintenance and Calibration

CNC technicians specialize in equipment health and metrology alignment. These experts ensure machines are calibrated to meet ISO 17025 lab requirements and handle spindle alignments, probe recalibration, and thermal compensation settings.

Quality Assurance in Testing Environments

Some machinists grow into QA specialists, developing procedures to reduce machining-induced sample defects like surface scoring or tool chatter, which can affect tensile or fatigue testing results. They also document traceability and work with test engineers to align fabrication output with research protocols.

CNC Equipment and its Place in Career Direction

Another key factor that must be considered and that shapes CNC operators' career paths in material testing is the type of equipment they work with. CNC machines vary greatly in generation, functionality, axis configuration, and manufacturer. From entry-level 3-axis mills used for simple flat specimen preparation to advanced 5-axis machining centers capable of complex geometries and multi-face operations, the equipment dictates both the complexity of the task and the level of skill required.

Operators in older labs may use traditional CNC mills with manual overrides and limited automation. Modern testing facilities often rely on newer systems with touchscreen interfaces, integrated CAD/CAM environments, automatic tool changers, and real-time error detection. There are a variety of machine capabilities, software platforms, and learning curves offered by different manufacturers.

Choosing the right facility or employer depends heavily on it. For instance, a lab preparing high-volume standardized tensile specimens might prefer machines optimized for repetitive accuracy, while a research center dealing with prototyping or non-standardized tests may use flexible, programmable systems.

As a result, CNC operators often tailor their training or certifications to match the specific machine types and controls they expect to work with. Understanding the type of equipment you will operate is more than just a matter of technical comfort - it can define your workflow, responsibility level, and potential advancement path within the material testing field.

Choosing the Right CNC System

At TensileMill CNC, we have spent years supplying CNC systems customized specifically for material testing laboratories and manufacturing environments. For CNC operators-whether beginners or experienced-the type of machine they work with can strongly influence their daily workflow and long-term career direction. That is why we developed the TensileMill CNC – Classic Upgrade: a system built to deliver high precision with exceptional simplicity.

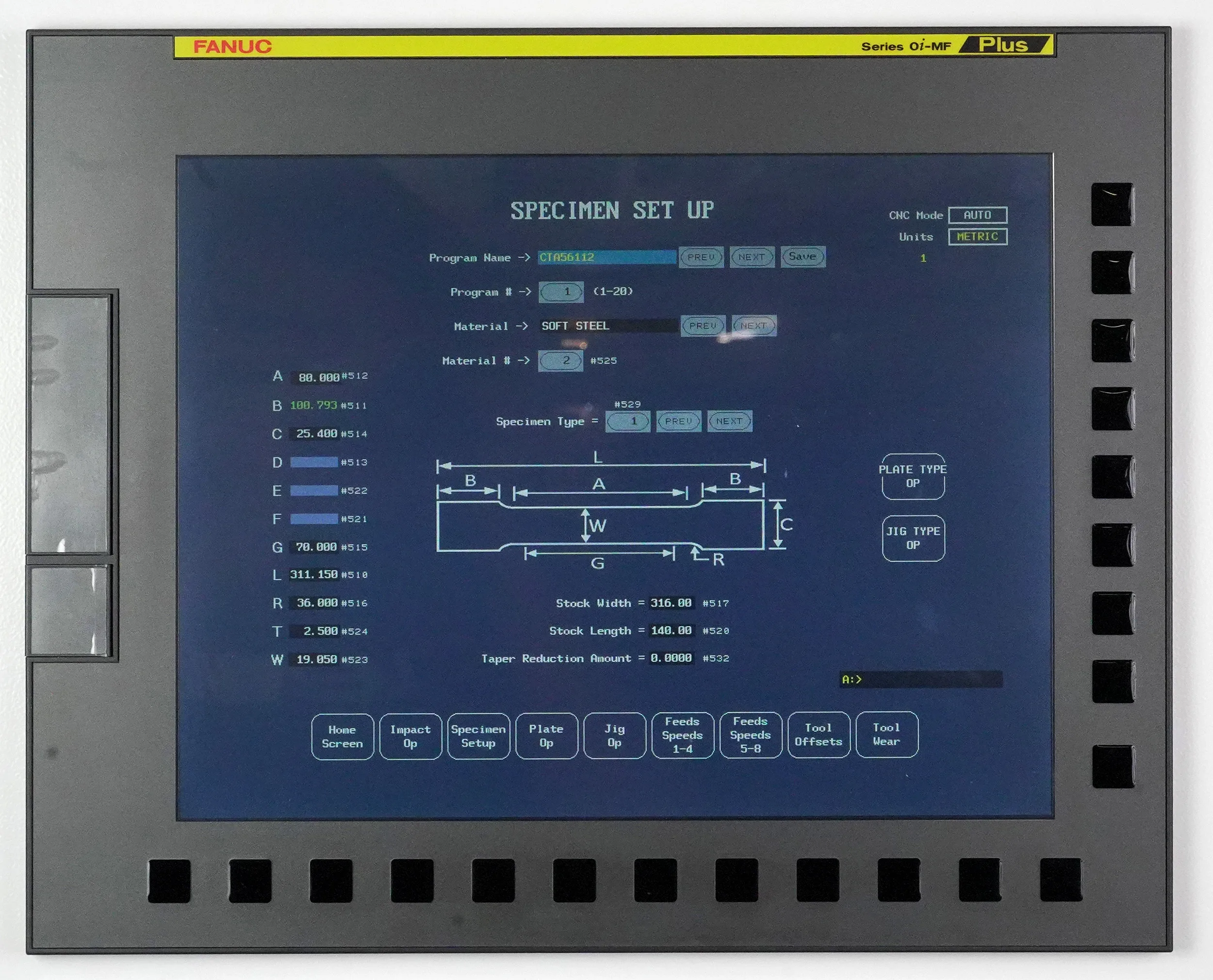

If you are looking for a machine that does not require extensive CNC experience to operate, this is the ideal solution. Thanks to our intuitive TensileSoft™ interface and FANUC touch screen controller, even machinists with minimal training can prepare flat tensile and Charpy impact samples with confidence. It is designed for fast onboarding, which makes it suitable for both high-throughput testing laboratories and educational settings.

The Classic Upgrade is the first hybrid CNC system that allows for accurate and repeatable preparation of both tensile and impact test specimens. It supports specimens up to 350 mm in length and 12.5 mm in thickness, with surface roughness tolerances under 75Ra-fully compliant with ASTM E8 and E23, ISO, DIN, and JIS standards. Its high-performance 3.2 kW motor and rigid cast iron frame ensure repeatability within ±0.02 mm, even when processing hardened materials up to 60 HRC.

With the ability to prepare up to 8 samples at once, and no requirement for additional surface grinders, this machine represents a turnkey solution. Operators benefit from reduced setup time, zero chatter, and consistently clean finishes-saving up to 90 percent of typical preparation time.

Final Thoughts on Building a CNC Operator's Career in Material Testing

A career as a CNC operator in the material testing field offers a structured and rewarding path that combines precision, technology, and real-world impact. From shaping the very first sample to influencing test reliability, CNC machinists are indispensable to modern quality control and research processes. The skills required-ranging from technical programming to equipment maintenance-make this role both intellectually engaging and highly valuable.

As laboratories and manufacturing environments continue to modernize, the demand for skilled CNC operators capable of working with advanced systems is steadily increasing. Choosing the right machine, training path, and facility will significantly influence an operator’s career development, opportunities for specialization, and overall growth within this evolving industry.

If you are looking for advanced CNC machines customized for material testing applications, please contact us directly or request an online quote. Let us assist you in making the right choice for your testing needs.